Background

Global total eclipse map. Source: Astronomy magazine

Oregon eclipse totality map. Source: Xavier Jubier

Solar eclipses are rare events, and total solar eclipses even more special.

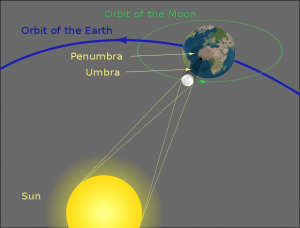

And we are very fortunate to live on a planet where eclipses happen at all! By purely lucky coincidence, our (relatively large) moon is the right size, and orbits at the right distance, to appear almost exactly the same diameter as the Sun, roughly 0.5 degrees of arc. Earth is the only planet in our solar system where solar eclipses occur.

However, the moons orbit is elliptical, not circular, and if an eclipse occurs when the moon is too far from Earth, then the moon appears too small to completely cover the sun. The result is an annular solar eclipse.

Annular solar eclipse, when the moon is too far from the Earth to completely cover the Sun. Source: Wikimedia

Geometry of total solar eclipse. Source: Wikimedia

If you are not in the correct place on Earth to perfectly line up the sun and moon, then you will see a partial eclipse. And an eclipse can only occur during the new moon phase, when the moon is in the same direction in the sky as the Sun.

However, when the Earth, moon, and Sun line up, the moon is relatively close to Earth in it’s orbit, you position yourself in the right place at the right time, and the weather is good, only then is it possible to see a total solar eclipse.

Every 18 months a total solar eclipse happens somewhere on Earth, but the Earth is a big place that’s mostly covered by water, so when an eclipse happens relatively close to you you should seize the moment and get after it.

However, procrastination also happens, and despite the years of advance notice that a solar eclipse would occur August 21, 2017, across the entire United States, the actual planning for this trip didn’t happen until the middle of July. Fortunately, it’s possible to make up for a lack of advanced planning by being flexible and having a self-contained, minimalist approach to life in general and travel in particular.

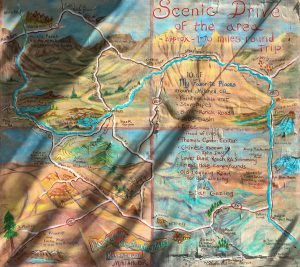

But we still need to pick a spot on the path of totality, which is about 100km wide and several 1000km long. We have several criteria for picking the location.

- within reasonable driving range of our home in Calgary

- one day’s drive from the southern Okanagan in B.C., where our friend Marc is coming from

- excellent chance of clear weather

- far from major population centers, since there are expected to be large crowds for this historic event

- BLM land camping, since every campsite along the path of totality has been booked at least a year in advance

- some interesting terrain nearby to explore by mountain bike

- good micro-brewed beer available nearby

At first we are looking at somewhere within the states of Oregon or Idaho, but those are big places, and further refinement leads us to the Oregon plateau, which is a fairly high and dry region in the rain shadow of the Cascade mountains. On Thursday night we decide that tomorrow we will point the Westy S.E. of Hood River, Oregon towards the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument.

Friday, Aug 18

We leave Hood River this morning, load up on food and water for four days and then drive east along the Columbia River gorge. The gorge is famous for its consistent, strong winds blowing up-river from the ocean, making it mecca for wind and kite surfers.

At Briggs Junction we leave the Columbia river and head south, as the road climbs up out of the gorge and into a veritable forest of wind mills, scattered around vast crop fields, turning majestically and transforming the strong winds into clean energy.

The immense Cascade volcanoes dominate the landscapes of western Oregon and Washington, rising at least 2500m above the surrounding highlands and nearly 3000m above the Columbia River. While Mt. Adams last erupted in 550BC, Mt. Hood is more active, and has erupted three times in the last 1800 years. The major Cascade volcanoes are all considered active, and the last major eruption occured in 1980, when Mt. St. Helens blew itself apart, creating one of the largest landslides ever recorded, destroying 100s of square kilometers of forest, and killing 57 people.

On this trip I learn that traveling with a VW Westfalia is a bit like traveling with a dog: it’s all about the Westy. Westy owners are fanatics about their machines, you’re always stopping to feed and water the thing, taking pictures of it, talking about it for hours, and anytime you see another Westy you need to stop and let them sniff each other.

As we continue heading south and east the landscape slowly changes from vast fields of grain covered in windmills to a more barren landscape of scrub brush and dry forest. We drop down in to the valley of the John Day River, cross the river at a small bridge and turn off the main road onto a secondary road which soon turns to gravel, which we continue following for around 20km.

It’s late in the afternoon before we find a flat spot on the side of the road and pull the Westfalia over for the night. We are “here”, where ever that is.

Saturday, Aug 19

We found out last night from two friendly Oregon state troopers that we were illegally camped and so this morning we pack up and continue down the gravel road, eventually finding a flat spot under a tree in a broad opening full of dry grass. And dry cow patties. Like back home in Western Canada, the fire hazard is extreme here, and we are very careful not to go through any tall dry grass for fear of igniting it with the hot exhaust.

Cars have been coming into this region all of yesterday and this morning, and there are already a couple groups camped in this spot to watch the eclipse. We walk over and say hi to our neighbors Dave, who has already set up his beautiful 10″ Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, and his friend Joe, who has a bad ass jeep covered in gun stickers and a tattoo on his arm from the local Rogue brewing company.

There has been no cell phone coverage for the last 50 miles or so, and after setting up our camp we head to the town of Mitchell to try and get some messages out. In Mitchell we find that our cell phones do not work and the pay phone on main street is not working, but the friendly lady at the post office lets us use her phone. Also find excellent tacos for $3 each made by a Mexican family who have set up a tent to feed tourists.

Others are clearly gouging the hoards of tourists but not these folks. Run into a San Francisco Bay Area astronomy club setting up a bunch of telescopes. The tiny town has a real festival feel, and has likely not seen this kind of activity in decades, if ever. The town of Mitchell used to be called Tiger Town in the late 1800s as the lower Main Street was bars and brothels while the upper bench was pious.

We spend the afternoon wiring a proper plug for the fridge in the van, since the cigarette lighter power plug is wrecked. That takes a few hours, and afterwards we head down to Priest Hole Recreation area on the John Day river. Already on Saturday the place is packed with at least a 100 cars, more tents, and dozens of telescopes of all sizes including a home made refractor at least 8′ long. We go for a swim in the river, a nice way to cool down, but then have to climb 800′ up the dusty gravel road on our bikes, around 2 miles back to camp.

We head back to Mitchell in the early evening to charge the Vanagon batteries and send a message to Marc with our camp location. Pat at the Spoke’n Hostel (pay by donation) is one of the friendliest guys I’ve ever met and offers us the use of their shower and access to wifi, so I can send our camp location to Jean, who then forwards it to Marc. Technology issues resolved. Hopefully Marc finds us tomorrow!

From the town of Fossil, Oregon: head south on 19 then turn right (west) towards Twickenham. Cross the creek and take the road right immediately after the bridge. Road turns to gravel after a few miles. Follow gravel road as it contours up and then back down for maybe 20km. Feels like you’re in the middle of nowhere. You are. At the junction to Priests Hole stay left. Do NOT go to the hole. 100s of people camped there already. We are on the left in a brown Vanagon about 1km past the Priests Hole junction. Last cell coverage is in Condon.

On the way back to camp, most of the way from Mitchell to nowhere, we get a flat tire. No spare and it’s nearly dark. We discuss options and hunt around for a big rock to prop up the jack. Dan gets to work jacking up the van while I hitchhike a ride the one kilometer back to camp to see if I can find some help. Our neighbors Dave and Joe and other neighbor Brian walk out to meet me as I get out of the car and walk over to ask for help. Jeep guys like Joe are often well prepared for backcountry vehicle self-sufficiency, and we are in luck, as he has a Blackjack tire repair kit and a small battery powered air compressor!

Joe drives us down to the van and gets to work. First the tire bead needs to be reset since it came off the rim as Dan was moving the van to the edge of the road. We spray the bead with water which helps it hold air and inflate it with the compressor and pop! the bead snaps back out to the edge of the rim. First step!

That progress is followed by a hissing sound as air rushes out a dime-sized slash in the inner sidewall of the tire. The Blackjack repair kit includes strips of gooey tar-like material that you push into the puncture with a big fat needle and then try and convince the goo to stick to the inside of the tire and fill the hole. Joe and Dave are concerned that this large sidewall puncture is too big for the goo to fill, but we work on it for about 20 minutes, in the light of Joe’s jeep, and eventually get it to hold air! Whoops of joy as the tire pressure builds.

The final step is putting the wheel back on the axle, which is made far more difficult than it needs to be by the ridiculous VW design of having bolt holes in the axle mounting plate instead of just bolts like every other vehicle. After much effort in the dark we finally get the wheel aligned and the bolts threaded and on. Gently lower the van off the jack and weight the tire, and it holds! Unbelievable, it’s fixed! We slowly drive up the road and make it to camp, jack the van corner up to take the weight off the tire, and Dan gives Joe and Dave the big growler of beer we purchased in Mitchell as thanks for saving our (Canadian) bacon. It’s fully dark now and the Milky Way is a glorious band arcing across the sky from north to south as we cook up our steak and veggies and rice for dinner.

Hercules globular cluster, M13, roughly as seen through a big telescope. Credit: Wikipedia

Galaxies M81 and M82. Source: Wikipedia

After dinner I wander over to see if Dave has his big telescope out, and sure enough he’s out star gazing. The Hercules globular cluster looks like a million tiny specs of bright dust clumped in a ball. Also our nearest big galactic neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy, Saturn, twin galaxies M81 and M82 in Ursa Major, triple stars on the Big Dipper handles, and some clusters in the Sagittarius region.

Seeing deep-sky objects “live”, through a telescope, is very different than browsing astronomical images on the internet. The view through a telescope is generally not as good, because our eyes are not as sensitive to light as cameras, and a camera can collect light for hours to form a single image. However, the reality of the situation is stunning, when you actually see the glorious rings of Saturn with your own eyes, or see a galaxy like M81, so far away that the light takes 12 million years to arrive here on Earth.

Sunday 20th

We go for a morning ride, following a dirt road up the ridge to the east and end up chatting for an hour with Charlie, who had parked his camo-painted and lifted Toyota 4×4 on the ridge, and has a big dog who barks at all who pass. We start to chat, start talking politics, and find out that Charlie is someone who is trying to save his country from Trump. We become fast friends, and an hour later are still chatting instead of riding our bikes.

Charlie is a wildlife biologist and military veteran, and we talk about health care, society, democracy, wilderness and life in general. I walk around his truck to talk to his dog, who is wisely napping in the shade, and see a big revolver in a holster on the ground, but somehow that feels normal here in the wilds of Oregon. We promise him beer if he comes down to our camp, and ask if we can join him in the morning to watch the eclipse.

It’s too hot to do much in the afternoon, so we hang out in the shade of our tree, clean the bikes and Dan plays guitar. Down time. A great thing to have on vacation.

We are also waiting for our friend Marc to show up. Marc left Penticton, B.C. yesterday afternoon, and we are expecting him to arrive sometime this afternoon. Yesterday we managed to send Marc directions on how to get to our camp, so today, here in camp without cell phone coverage, we need to just hang out and wait for him.

Around 3:00 in the afternoon Marc shows up, and the first words he says are “wow, you could not have picked a more remote spot!”. We laugh, welcome him to Tree Camp and say, yeah, being remote was the goal!

In the early evening we ride up the ridge again to visit Charlie and bring him some beers. The ridge has views in all directions, and we have a great time chatting with Charlie while watching the sunset cast long shadows across the landscape. The evening sky is somewhat cloudy, and while we are all excited about the eclipse tomorrow, we are also concerned about the clouds that have moved in. Every flat spot on the ridge road has a vehicle on it, as well as every spot in the valley here in this usually remote and empty place. It’s fun to see how many people are so enthusiastic enough about this event to make the effort and come out here to the middle of nowhere to witness the eclipse.

In the evening Dan makes pasta dinner and we invite neighbor California Dan, who’s camping by himself 20m away from us, to join us. Marc and Dan jam on guitar after dinner and Joe strolls over, then Nick and Angeline from Seattle, and we have an impromptu party under the stars in the middle of nowhere, Oregon.

The sky has been cloudy most of the afternoon, but fortunately clears up steadily and by 10:00 is completely clear and the Milky Way is stunning overhead, arcing from north to south. I set up the star tracker to capture the scene, and Nick and Angeline hang out with me as we shoot the stunning night sky. Turns out that California Dan also has a telescope, a 12″ Newtonian reflector on a Dobsonian mount, and later in the evening we wander over to his camp to enjoy the views through the big scope.

Note to self: buy a green laser pointer!

Monday, Eclipse Day

This is the day! All this planning and traveling have been to get here, in the path that the moon’s shadow will trace across the surface of the Earth. Today. This is it.

Eclipse morning and the sky is clear blue and we are up at 7. Breakfast is quick and we pack up to hike / bike up the ridge to the west. We are up on the ridge by 8:30 or so. Charlie’s dog Poppy comes running out to greet us and runs right past me to Dan. Nice to see you too, Poppy! We chat with Charlie for a bit then continue hiking up the ridge road to the top, to look down into the John Day river valley.

At the top of the ridge we chat with UK Charlie and Swedish Annette, who have a small refractor set up on a compact iOptron mount with a cool center-mounted polar alignment scope. The views of the John Day river down in the valley with the painted hills behind and the swarms of people camped along the river are fantastic in the morning light. Just before 9 we stroll back to Oregon Charlie’s camp, where we have left our gear to wait for the beginning of the eclipse.

Like in western Canada, the summer here in Oregon has been exceptionally hot and dry, and there are a few wildfires in the region that send streamers of blue or yellow smoke across the sky. These smoke streams and some light clouds are moving in from the south, and we hope that they will not disrupt the eclipse too much, because it’s too late to try and move now.

Just like protecting your eyes, it is absolutely critical to have a proper solar filter to protect the camera when photographing the sun with a big lens. My friend Kai is a master wood-turner, and I was thrilled when he made a beautiful wooden filter holder for me. It fits snugly over the front of the lens, and looks fantastic, giving the camera an Earthy, rustic feel. All of the partial-phase solar eclipse images, at left, are taken through the solar filter.

The filter material itself is a black polymer film made by Thousand Oaks Optical. It is a low cost and effective solution, but fragile, and only passes 1/1000th of 1% of the sun’s light.

We are all just hanging out on the ridge this morning, chatting about the weather, checking our watches and putting on dorky eclipse glasses to glance at the sun every few minutes. There’s a real excitement in the air, but otherwise it’s just a relaxed sunny morning in the middle of nowhere.

At 9:10 a small dimple appears on the edge of the sun – first contact of the moon, and the eclipse has begun! The light clouds and smoke are above us now, but are not too thick, just a thin haze that does not disturb the view of the sun.

Over the next hour the moon slowly drifts across the face of the sun, two perfectly aligned disks. First contact generated much excitement, but for the next hour people relax again, chatting, looking up at the sun, taking photos, pointing out a line of sunspots. With careful observation, the full circle of the moon can be imagined being visible as it is silhouetted against the face and the atmospheric glow of the sun. The camera does not capture that, however, so I’m wondering if it actually was visible, or just an illusion as your mind fills in the blank space occupied by the moon.

At about 1/2 coverage it starts to get noticeably cooler and by 3/4 coverage the character of the light around us starts to change, becoming softer and darker. A wide angle shot of the sky reveals a darkness to the west as the moon’s shadow approaches. We hiked up this ridge with the hope of seeing the approaching shadow and there it is!

The environment starts to change faster and faster as the two limbs of the crescent sun slowly disappear behind the moon. It is very noticeably cooler now and the light on the ground becomes very soft and mellow. The air is perfectly still; we are surprised that there is no wind caused by the cooling air.

Wildly out-of-scale diagram showing the umbra (total eclipse) and penumbra (partial eclipse) regions. Source: Exploratorium

As the last crescent of the sun gets consumed by the moon the darkening and cooling increase. Suddenly we notice that the sky in the west is very dark, like an approaching storm. That darkness is the umbra of the moons shadow, approaching us at over 3000km/h.

I had repeatedly read that during your first total eclipse you should just watch the event and not try and photograph it, but naturally I ignored that advice and am busy capturing as much of this incredible spectacle as I can, quickly swapping the camera from a 400mm lens for details to an extremely wide fisheye lens to capture the incredible environment of sky and land.

The sun is almost completely covered by the moon now, with only a tiny sliver remaining, but even that is still far too bright to look at without the solar glasses. The landscape is dark like during sunset, but without the yellow / red colors, just soft light, and the shadows, normally long and horizontal at sunset, are short, vertical, mid-morning shadows.

Then, in an instant, the sun winks out, and is replaced by a black disk with the bright white streamers of the corona reaching out like delicate flower pedals. The solar glasses come off and you can look straight at the flowery black hole where the sun was. Bright stars and planets are visible in the sky and everyone around us is whooping with complete awe at the absolutely incredible sight above us and the magical light all around, as if sunset and nighttime were compressed into one sky.

Totality is indescribably beautiful.

The transition from what felt like a not-quite-right twilight to the utterly alien scene of a glowing black hole high in an otherwise dark sky was incredibly quick. The moment that the sun blinks out – an unfathomable event that we all intellectually expected, but still felt so wrong – is an overwhelming sensory shock to the system. The image of that alien sky is still burned in my eyes weeks later.

I capture a few frames of the corona with the big lens, bracketing the exposure a bit, while Marc, Dan and Charlie, along with everybody else on the ridge, are whooping and hollering and taking their own photos, and then quickly swap the fish-eye lens on the camera to capture the surreal environment all around us.

Suddenly wham, like being caught in a spotlight, the lights come on again as the first speck of the sun re-appears from behind the moon.

Totality lasted just over two minutes, but seemed like only two heartbeats.

Illustration of the Sun and Earth, showing the interaction of the solar wind and with the Earth’s magnetosphere. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Solar physics

The corona is the Sun’s outer atmosphere, and is only visible during a total eclipse because it is only about 1/1,000,000 as bright as the surface of the sun. Between 1 million to 5 millions Celcius, the corona is also much hotter than the surface of the sun, but the exact mechanism of that extreme heating are still the subject of scientific debate.

Also visible in the above image are two solar prominences, at about the 1:00 and 3:00 positions. A solar prominence is a loop of hot stellar material erupting from the surface of the sun, usually following magnetic field lines. The loops are often 100s of thousands of kilometers in length, much larger than the Earth!

The corona is also the source of the solar wind, a flow of highly energized, charged particles that reaches all the way to the edge of the solar system.

The solar wind can carry more than one million tons per second of material away from the sun and as these particles stream past Earth, they are moving at around 400 kilometers per second. Most of the particles are deflected around the Earth by our planet’s magnetic field, but occasionally some make it as far as our atmosphere, causing auroras around the north and south magnetic poles.

Earth’s magnetic field is responsible for saving our atmosphere, and fragile creatures like us, from this torrent of charged particles. Recent observations by NASA’s MAVEN mission have revealed how the solar wind slams into Mars, which has a much weaker magnetic field than Earth, and strips particles from its atmosphere.

The corona of the Sun is beautiful, and it’s very rare and special to see it, but life on Earth would not exist as we know it without the magnetic field surrounding and shielding us from the deluge of particles flowing from the sun.

Cosmic physics

The bending of star light around the sun. True position of distant star is A, while observed position is at B. Image source: Physics of the Universe

The Illustrated London News, November 22, 1919. Source: Eclipse-maps.com

Total solar eclipses are rare, visually stunning and emotionally powerful events, but they have also enabled some truly world-changing science experiments.

Albert Einstein’s famous general theory of relativity has revolutionized our concepts of gravity, space and time, but in 1919 it was a new theory by an unproven physicist. One of its key predictions is that light would follow a curved path around a large, massive object. The Sun is certainly a massive object, and so the position of distant stars should change very slightly when their light passes close to the Sun. The problem is that the Sun is so bright that it overwhelms the light of stars.

The solar eclipse of May 1919 provided the first opportunity to test Einstein’s prediction, and two expeditions were launched from England by Sir Arthur Eddington. One went to the island of Principe, off the west coast of Africa and the second to Sobral, Brazil, to photograph the eclipse and precisely measure the positions of stars close to the sun.

The results of Eddington’s observations matched the predictions and provided the first evidence to support Einstein’s radical theory. The finding made newspaper headlines, made the theory of relativity world famous, and made Einstein a scientific celebrity. Of course, the experiment was repeated during the 1922 eclipses, and numerous times since then, with the results in good agreement with the 1919 observations.

The moon’s shadow, from orbit around the moon. Credit: NASA, GSFC, Arizona State University, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

The Big Picture

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter took this image of the Earth, from around 384,000km away, which shows the moon’s shadow as it sat on the eastern coast after it finished crossing the United States. Another spectacular image in the Astronomy Photo of the Day collection.

Photographic lessons

I had a 400mm lens, which worked fine, but an 800mm would be ideal to image the corona. Also more bracketing of the exposures to capture the extremely wide dynamic range of the corona.

The dynamic range of the scene is extreme! French photographer Nicolas Lefaudeux did an incredible job of capturing the event, and the eclipse images on his website are truly stunning.

More than one camera, and more than one photographer, would be great. Ideally three cameras. One needs to be focused on capturing the detail of the sun with a big telephoto lens (or small telescope) of at least 600mm focal length, over a wide range of exposure values. The other one needs to have as wide a lens as possible, in order to capture the rapidly changing light on the landscape as the moon’s shadow approaches and the sun disappears. It would also be fun to have another camera capturing the entire scene, including the expressions and emotions of the people during this incredible event.

This is definitely not be the only eclipse I will see! The next “easy” total solar eclipses are passing over Chili and Argentina in 2019 and 2020.

See you there.

Darren Foltinek, August 2017